Introduction

Rotavirus is a double-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Reoviridae. It is the most common cause of severe gastroenteritis in infants and young children worldwide. Despite the availability of vaccines, it remains a significant public health concern in low-resource settings due to its high infectivity and potential to cause severe dehydration.

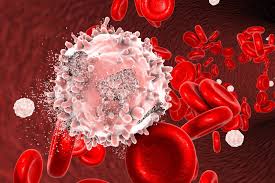

Virology and Structure

Virus Structure:

Genome:

Composed of 11 segments of double-stranded RNA, which encode six structural (VP1-VP4, VP6, VP7) and six non-structural proteins (NSP1-NSP6).

Capsid:

Triple-layered structure that provides stability and protects the genome:

Outer Layer:

VP4 (spike protein) and VP7 (glycoprotein) are critical for immune response and vaccine design.

Inner Layer:

VP6, the most abundant protein, is used for diagnostic tests.

Core Layer:

VP1, VP2, VP3 are involved in replication and transcription.

Classification:

Rotaviruses are divided into A–H groups, with Group A causing the majority of human infections. Further classification into G (VP7) and P (VP4) genotypes is based on surface proteins.

Epidemiology

Global Impact:

Global Impact refers to the far-reaching consequences of actions, events, or phenomena that transcend national borders, influencing economies, societies, environments, and technologies worldwide. In today’s interconnected world, decisions in one region often ripple across the globe, as seen in climate change, global trade, technological innovations, or pandemics.

For instance, greenhouse gas emissions from industrialized nations affect weather patterns globally, while economic policies in major economies can shift markets worldwide. Similarly, advancements in artificial intelligence and renewable energy are reshaping industries across continents.

Addressing global challenges like inequality, environmental degradation, and health crises requires collective action, fostering international collaboration, sustainable practices, and innovative solutions to ensure a resilient and inclusive global future.

Causes an estimated 200,000 deaths annually, mostly in low- and middle-income countries. Accounts for nearly 40% of diarrhea-related hospitalizations in children under five.

Age Susceptibility :

Age Susceptibility refers to the varying degrees of vulnerability or responsiveness individuals have to diseases, environmental factors, or certain conditions based on their age. Different age groups experience unique susceptibilities due to biological, physiological, and developmental factors

. For instance, infants and young children often have underdeveloped immune systems, making them more prone to infections, while older adults may face increased risks of chronic illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, or cognitive decline due to aging processes.

Age susceptibility also influences the effectiveness of medications, vaccines, and interventions, emphasizing the need for age-specific healthcare strategies. Understanding these vulnerabilities is crucial for tailoring prevention, treatment, and public health policies to meet the needs of diverse age groups effectively.

Primarily affects children aged 6 months to 2 years. Adults can be infected but typically experience milder symptoms.

Seasonality:

Common in cooler months in temperate climates. Occurs year-round in tropical regions.

Transmission:

Highly contagious, primarily spread via the fecal-oral route. Virus is excreted in large quantities in stool and can contaminate surfaces, water, and food.

Pathophysiology

Infection Site:

Infects and destroys mature enterocytes in the small intestine, leading to malabsorption and osmotic diarrhea.

Mechanisms of Disease:

Malabsorption:

Loss of villous epithelial cells reduces nutrient absorption.

Secretory Diarrhea:

NSP4 acts as an enterotoxin, causing increased fluid secretion.

Increased Gut Permeability:

Leads to loss of water and electrolytes.

Immune Response:

Inflammatory mediators exacerbate damage.

Clinical Presentation

Incubation Period:

Typically 1-3 days after exposure.

Symptoms:

Diarrhea:

Profuse, watery stools (non-bloody). Vomiting: Often occurs before diarrhea begins.

Fever:

Low to moderate grade.

Abdominal Pain:

Common but not always severe.

Dehydration:

A critical concern, especially in young children.

Signs include:

Sunken eyes, dry mouth, decreased urination. Lethargy or irritability.

Duration:

Symptoms typically resolve in 3–8 days without complications.

Severe Cases:

Persistent vomiting and diarrhea can lead to life-threatening dehydration, especially in malnourished children.

Diagnosis

Clinical Evaluation:

Based on symptoms and age group. History of exposure to known cases or contaminated environments.

Laboratory Tests:

Stool Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA):

Detects rotavirus antigens.

Reverse Transcription-PCR (RT-PCR):

dentifies specific genotypes.

Electron Microscopy:

Visualizes the virus (rarely used due to cost).

Rapid Tests:

Commercial kits for quick diagnosis in clinical settings.

Treatment

There is no antiviral treatment specific to rotavirus; management focuses on symptom relief and preventing dehydration.

Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT):

First-line treatment for mild to moderate dehydration. Contains balanced salts and glucose to replenish fluids and electrolytes.

Intravenous Fluids:

Required for severe dehydration or when ORT is not feasible.

Zinc Supplementation:

Recommended by WHO to reduce the severity and duration of diarrhea.

Nutritional Support:

Continue breastfeeding or normal diet to prevent malnutrition. Avoid sugary or fatty foods that can worsen symptoms.

Prevention

Vaccination:

Rotavirus vaccines are the most effective prevention strategy.

Two main vaccines:

Rotarix (RV1):

Two-dose series (oral).

RotaTeq (RV5):

Three-dose series (oral). Administered starting at 6 weeks of age, with completion by 24 weeks.

Hygiene and Sanitation:

Handwashing with soap and water. Proper disposal of diapers and waste. Disinfecting surfaces and shared objects.

Breastfeeding:

Provides temporary immunity and reduces severity in infants.

Improved Water Quality:

Reduces fecal-oral transmission.

Complications

Severe Dehydration:

Can lead to shock, organ failure, and death if untreated.

Electrolyte Imbalances:

Resulting from excessive fluid loss.

Secondary Infections:

Due to weakened intestinal barrier.

Intussusception:

Rarely associated with rotavirus vaccines but occurs less frequently than the natural disease itself.

Research and Future Directions

Next-Generation Vaccines:

Efforts to develop vaccines that are more thermostable and effective against all strains.

Antiviral Therapies:

Investigations into drugs targeting rotavirus replication.

Global Health Strategies:

Expanding vaccine coverage in low-resource settings. Improving water and sanitation infrastructure.

Conclusion

Rotavirus remains a leading cause of pediatric morbidity and mortality, particularly in low-income regions. Early diagnosis, prompt rehydration therapy, and vaccination are essential to reducing its global impact. Ongoing research into improved vaccines and treatment options offers hope for further control of this disease.